How To Test Your Distributed Message-Driven Application With Spring?

Messaging is cool. It allows to deal with a broad set of various problems that developers face on a daily basis. It is not a silver bullet though. One must assess if their architectural drivers fit this pattern. A list of tips that might help you with this decision:

- Communication between some components needs to be asynchronous - producer fires and forgets.

- Consumer should process the messages at its own pace - independent from producer’s pace. This is so-called throttling.

- Communication should be reliable - message broker can store and forward messages. Thus, producer does not need to care about retrying.

- We deal with occasionally connected devices. Those are component that tend to be offline or down but need to synchronize as soon as the reconnect. Disconnection must not affect the producer. The need for two components to be alive at the same time is called temporal coupling.

- There is a need for multicast/broadcast.

- One of our components uses event sourcing. You can learn about that concept listening to this talk.

- There is already a production setup of a message broker in your infrastructure.

Note that those are mosty tips at distributed level. One can think about benefits of having messaging in monoliths architectures too. Like Inversion of Control - a way to continue a business process in a different part of same application. Or concurrency control implemented in actor model. An actor has its internal queue of messages processed one at a time. In this article we will read about testing message-driven systems in distributed syastems. Systems which use messaging as transport mechanism (first five tips) and event sourcing.

Let’s imagine an enterprise that issues credit cards under one condition - a potential client’s age. There is a REST API to do so:

@RestController("/applications")

class CreditCardApplicationController {

private final ApplyForCardService applyForCardService;

CreditCardApplicationController(ApplyForCardService applyForCardService) {

this.applyForCardService = applyForCardService;

}

@PostMapping

ResponseEntity applyForCard(@RequestBody CardApplication cardApplication) {

return applyForCardService

.apply(cardApplication.getPesel())

.map(card -> ok().build())

.orElse(status(FORBIDDEN).build());

}

}

And an application service responsible for the decision:

@Service

class ApplyForCardService {

private final CreditCardRepository creditCardRepository;

ApplyForCardService(CreditCardRepository creditCardRepository) {

this.creditCardRepository = creditCardRepository;

}

@Transactional

public Optional<CreditCard> apply(int age) {

if (bornBeforeSeventies(age)) {

return Optional.empty();

}

CreditCard card = CreditCard.withDefaultLimit(age);

creditCardRepository.save(card);

return of(card);

}

}

Imagine a new business need. System must react to a certain decision. If a card is granted, system must deal with that fact in a particular manner. If a card application is rejected, it must do something else. Whatever it is. It might be an email, an update in a reporting tool or anything else. But this process continues in a different application in the distributed environment. Plus this application can be temporary offline. Of course, it should not affect the granting/rejecting process. Did I mention that there is a huge probability that more applications would like to know final result of the process?

By now, it should be clear that messaging might be a good fit for this problem. We will add one line of coded escribing what has happened. A message saying that either the card was granted or the application was rejected. Nothing more. A special kind of a message that represent a fact in a past is called an event. We need a component that will be responsible for publishing those events. Its responsibility is clear, but let’s postpone the implementation. Additionally, there might be several ones, so let’s add an interface for the time being:

interface DomainEventPublisher {

void publish(DomainEvent event);

}

interface DomainEvent {

String getType();

}

DomainEvent interface contains only an information about the event’s type. This might be handy while distributing or subscribing to specific messages.

After you, dear test

Any production code that is not proved by a test is just a rumour, so here goes an unit test:

def 'should emit CardGranted when client born in 70s or later'() {

when:

applyForCardService.apply("89121514667")

then:

1 * domainEventsPublisher.publish( { it instanceof CardGranted } )

}

def 'should emit CardApplicationRejected when client born before 70s'() {

when:

applyForCardService.apply("66121514667")

then:

1 * domainEventsPublisher.publish( { it instanceof CardApplicationRejected } )

}

And in order for the test to pass:

@Transactional

public Optional<CreditCard> apply(String pesel) {

if (bornBeforeSeventies(pesel)) {

domainEventsPublisher.publish(new CardApplicationRejected(pesel));

return Optional.empty();

}

CreditCard card = CreditCard.withDefaultLimit(pesel);

creditCardRepository.save(card);

domainEventsPublisher.publish(new CardGranted(card.getCardNo(), card.getCardLimit(), pesel));

return of(card);

}

Voilà. Let’s go to production. All tests are green and that means we are good to go. But ... the application does not start on my local machine. There is no spring bean that implements the DomainEventPublisher interface. The unit test might be useful to drive a good design. Especially if you are a mockist TDD practitioner. But it is clearly not enough. Communicating with an external infrastructure from a business code is rather an integration task, isn’t it? So how about an integration test? But do we want to have a dependency on a message broker in our tests? Does it need to run to build the application? Or should each of the developers have their own local instance of the broker? The answer to every of those questions is no. Tests should run in isolation. Let’s finally implement the interface. And let's test the whole process with an integration test.

We can use a wonderful tool - Spring Cloud Stream - to implement the messaging part. In short, this is a framework that abstracts messaging paths with so-called channels. Channels are bound to a specific broker’s destinations by classpath scanning. The tools looks for binders to Kafka or RabbitMQ. Let’s choose RabbitMQ. Our credit card application is a producer to one channel. That means it is a source for messages. Simillary, the consumer is a sink. We need to remove the dependency to a real broker in tests. To do so, we are going to replace the production implementation with @MockBean.

The integration test (in jUnit, because it is easier to use @MockBean in jUnit):

@MockBean DomainEventsPublisher domainEventsPublisher;

@Autowired CreditCardApplicationController cardApplicationController;

@Test

public void shouldEmitCardGrantedEvent() {

// when

cardApplicationController.applyForCard(new CardApplication("70345678"));

// then

verify(domainEventsPublisher).publish(isA(CardGranted.class));

}

@Test

public void shouldEmitCardApplicationRejectedEvent() {

// when

cardApplicationController.applyForCard(new CardApplication("60345678"));

// then

verify(domainEventsPublisher).publish(isA(CardApplicationRejected.class));

}

Implementation:

class RabbitMqDomainEventPublisher implements DomainEventsPublisher {

private final Source source;

RabbitMqDomainEventPublisher(Source source) {

this.source = source;

}

@Override

public void publish(DomainEvent domainEvent) {

Map<String, Object> headers = new HashMap<>();

headers.put("type", domainEvent.getType());

source.output().send(new GenericMessage<>(domainEvent, headers));

}

}

And listener at consumer’s side:

@Component

class Listener {

private static final Logger log = LoggerFactory.getLogger(Listener.class);

@StreamListener(target = Sink.INPUT, condition = "headers['type'] == 'card-granted'")

public void receiveGranted(@Payload CardGranted granted) {

log.info("\n\nGRANTED [" + granted.getClientPesel() + "] !!!! :) :) :)\n\n");

}

@StreamListener(target = Sink.INPUT, condition = "headers['type'] == 'card-application-rejected'")

public void receiveRejected(@Payload CardApplicationRejected rejected) {

log.info("\n\nREJECTED [" + rejected.getClientPesel() + "] !!!! :( :( :(\n\n");

}

}

Note the use of headers - this allows us to distribute messages to specific methods at the consumer’s side.

This time we are definitely good to deploy to production. We have both unit and integration tests. Let’s run the application on our local machine for the last time. ...and it failed for the same reason. No bean that implements the DomainEventPublisher interface. We forgot to register the implementation as a spring bean. But wait a minute, how come the integration test passes? Take a closer look at the @MockBean docs:

“Mocks can be registered by type or by bean name. Any existing single bean of the same type defined in the context will be replaced by the mock. If no existing bean is defined a new one will be added. “

Unit test vs Integration test

So the tool added the bean to the application context. Even though its real implementation was not there. And this is by design. We should have been more careful. Let's notice some facts about our new integration test:

- It setups the whole context.

- It is significantly longer than the unit test.

- It even uses an embedded H2 database by default.

- … but it still tests our messaging in the mockist’s way!

- … but it still can be green without the actual implementation (just like the unit test)

- … but still the communication with broker is not tested.

The architectural diagram is worth more than a thousand words so let’s take a look at two of those:

The left one shows what was tested by the unit test. Everything else is blurred. And the second one highlights what was tested by the integration test.

In both cases, the actual messaging (DomainEventPublisher) was not tested. Moreover, the integration test examines more not that essential components. Not essential, taking into account that DomainEventPublisher is still left untested. There must be a better way. Let’s take a deeper look at Spring Cloud Stream’s documentation. In a paragraph about testing we can find an interesting note:

“... we are using the MessageCollector provided by Spring Cloud Stream’s test support to capture the message has been sent to the output channel as a result. Once we have received the message, we can validate that the component functions correctly.”

Spring Cloud Stream Testing Support

So here it is! Testing support and in particular MessageCollector can help us test our code. Without a dependency to a real broker. Instead, the messages can be held in an internal in-memory blocking queue. Here goes the test:

@SpringBootTest

class ApplyForCardWithEventMessageCollectorTest extends Specification {

@Autowired CreditCardApplicationController cardApplicationController

@Autowired Source source

@Autowired MessageCollector messageCollector

BlockingQueue<GenericMessage<String>> events

def setup() {

events = messageCollector.forChannel(source.output())

}

def 'should be able to get card when born in 70s or later'() {

when:

cardApplicationController.applyForCard(new CardApplication(20))

then:

events.poll().getHeaders().containsValue("card-granted")

}

def 'should not be able to get card when born before 70s'() {

when:

cardApplicationController.applyForCard(new CardApplication(90))

then:

events.poll().getHeaders().containsValue("card-application-rejected")

}

}

That means we can finally use the same bean as in production code. We finally test the whole producer's side:

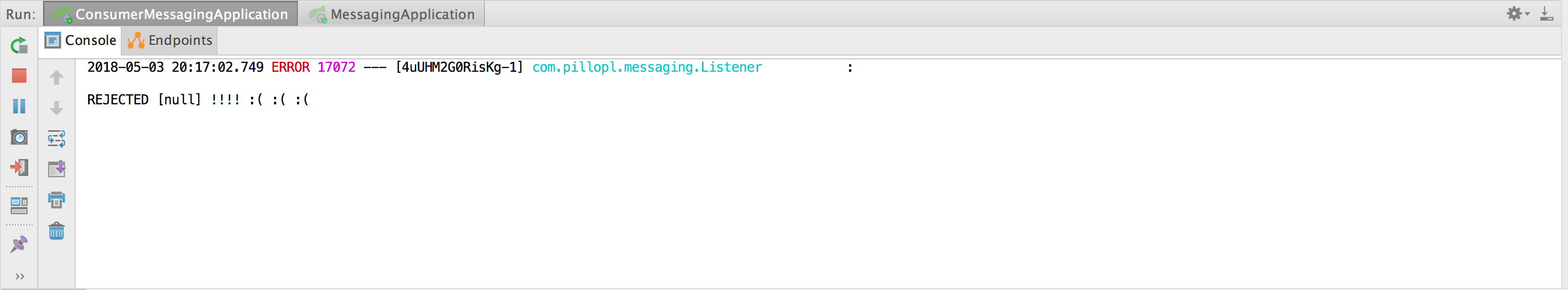

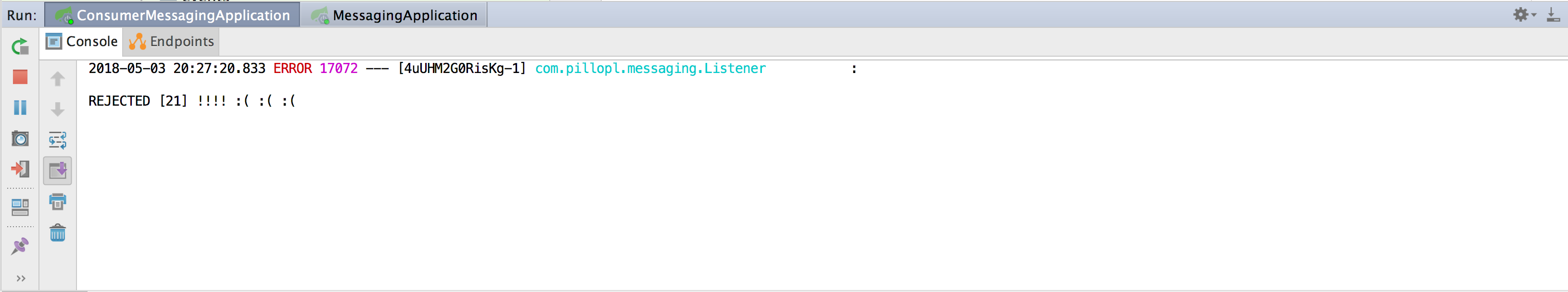

Our application is starting on our local machine! We can finally deploy to production. Just before doing so, let’s also start a consumer application and a docker image of RabbitMQ. Let’s trigger some messages and see them received at the consumer’s side:

It worked! Or did it? Wait a minute. The listener is able to get the message, but its content is empty! Why there is null value? What could have gone wrong? The complete test was created. Plus, it examines exactly the same path as the production code. But there is one thing that we need to know about it. MessageCollector captures the message in an internal queue before actual serialization. This serialization happens in the production code. It happens while sending a message to a channel! That leads us to a point that there must be something wrong with our serialization. The channel is configured to talk in JSON, so probably we need to help Jackson a bit. Let’s have a quick look at the classes that represent events:

public class CardApplicationRejected implements DomainEvent {

private final String clientPesel;

private final Instant timestamp = Instant.now();

public CardApplicationRejected(String clientPesel) {

this.clientPesel = clientPesel;

}

@Override public String getType() {

return "card-application-rejected";

}

}

A careful reader will quickly spot the problem. The getters are not there and Jackson by default will not serialize any field without a getter. Let’s fix that and rerun:

Success. It finally worked. The producer and consumer can communicate without issues. But does it mean there is no way of testing it without doing the manual check? Does it mean that each time we develop a message-driven system, we must set it up on a local machine? And manually prove its correctness? Of course not.

Spring Cloud Contract

To automatically test the whole process we would have to bring up the consumer side as a dependency. Plus a message broker. We have already said that this is not the best idea since we want to run tests in isolation. They should not be dependent on a presence of another component. Fortunately, there is a tool called Spring Cloud Contract. With this framework we can check if microservices will communicate on production environment. And all that without having to create a test that brings all of them up. Plus, it works with both messaging and REST APIs. Sounds like a perfect fit.

The producer declares a contract. It says that if there is a rejection of a card application, some message should be sent to a specific channel. The contract defines the body of that message:

label: card_rejected

input:

triggeredBy: sendRejected()

outputMessage:

sentTo: channel

headers:

type: card-application-rejected

contentType: application/json

body:

clientPesel: 86010156812

timestamp: 2018-01-01T12:12:12.000Z

matchers:

body:

- path: $.timestamp

type: by_regex

predefined: iso_8601_with_offset

The contract is packaged as a maven artifact. Based on that contract, a test is automatically generated. Its purpose is to check if the producer adheres to what is in the contract. It looks like this:

@Test

public void validate_shouldSendACardRejectedEvent() throws Exception {

// when:

sendRejected();

// then:

ContractVerifierMessage response = contractVerifierMessaging.receive("channel");

assertThat(response).isNotNull();

assertThat(response.getHeader("type")).isNotNull();

assertThat(response.getHeader("type").toString()).isEqualTo("card-application-rejected");

assertThat(response.getHeader("contentType")).isNotNull();

assertThat(response.getHeader("contentType").toString()).isEqualTo("application/json");

// and:

DocumentContext parsedJson = JsonPath.parse(contractVerifierObjectMapper.writeValueAsString(response.getPayload()));

assertThatJson(parsedJson).field("['clientPesel']").isEqualTo(86010156812L);

// and:

assertThat(parsedJson.read("$.timestamp", String.class)).matches("([0-9]{4})-(1[0-2]|0[1-9])-(3[01]|0[1-9]|[12][0-9])T(2[0-3]|[01][0-9]):([0-5][0-9]):([0-5][0-9])(\\.\\d{3})?(Z|[+-][01]\\d:[0-5]\\d)");

}

Note that the test examines the message body. So in our previous example, it would have spotted the problem with the lack of any getter. Plus, this test is fired each time we would build the producer application. Each version of a producer comes with a corresponding version of stubs defined in a contract. How cool is that?

Transaction semantics

Have you noticed any problem with the code that grants/rejects credit cards? Something about events, maybe? Let’s have a second look:

@Transactional

public Optional<CreditCard> apply(String pesel) {

// (...)

creditCardRepository.save(card);

domainEventsPublisher

.publish(new CardGranted(card.getCardNo(), card.getCardLimit(), pesel));

return of(card);

}

How to atomically save a newly created card to our database and send a message to our message broker? Remember that actual commit to the database takes place after returning from the body of this method. The proxy does that. Two-phase-commit is not an option because we don’t want to downgrade the performance. Let’s examine following scenarios:

- Sending to the broker failed. Database transaction rollbacks and everything is fine. Neither credit card nor message was saved.

- Sending to the broker was successful. Spring proxy tries to commit and database is down. The message was sent while the card was not saved.

One can come up with an idea of reordering the steps. First, let’s make sure that the card was saved. Only then we are entitled to announce that via event. This scenario can be implemented using a callback registered with TransactionSynchronizationManager. But what if the broker is not online? Or our application was killed between successful commit and callback execution? . The system will try to send that only once, it is crucial to understand that this is at-most-once guaranty.

What if we must send this message eventually? What if the requirement says that it must appear if a card was successfully saved? We can take advantage of the fact that most probably there is an ACID database in our toolbox. Let’s store both in one storage, using one transaction! A separate thread can take a look at all events saved in that storage and fetch ones not yet sent to the broker. Then send them and mark as sent. All in a couple of lines in new implementation of DomainEventPublisher:

@Component

public class FromDBDomainEventPublisher implements DomainEventsPublisher {

private final DomainEventStorage domainEventStorage;

private final ObjectMapper objectMapper;

private final Source source;

public FromDBDomainEventPublisher(DomainEventStorage domainEventStorage,

ObjectMapper objectMapper,

Source source) {

this.domainEventStorage = domainEventStorage;

this.objectMapper = objectMapper;

this.source = source;

}

@Override

public void publish(DomainEvent domainEvent) {

try {

domainEventStorage

.save(new StoredDomainEvent(objectMapper.writeValueAsString(domainEvent)));

} catch (JsonProcessingException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

@Scheduled(fixedRate = 2000)

@Transactional

public void publishExternally() {

domainEventStorage

.findAllBySentOrderByTimestampDesc(false)

.forEach(event -> {

source.output().send(new GenericMessage<>(event.getContent()));

event.sent();

});

}

}

Notice that the method which periodically publishes new events suffers from the same problem of lack of an atomic transaction. It tries to connect to the broker and to save state. But this time it is after successful card creation. And it has retries. If the broker is down, we will retry. After successful communication with the broker, the database can be offline. Hence, we will not mark the event as processed. We will resend it, implementing what is called at-least-once guaranty. Whether you should go with at-least-once or at-most-once depends on the business problem. For marketing purposes probably at-most-once is fine. But if a message carries a significant information (like how to activate the card), then probably the clients want that message. And will not mind getting it twice. At least they will be less angry than when not receiving it at all. And if your consumer is idempotent, then there is no problem at all.

Store only one thing

How we can deal with cooridnation of two different components? With database and with message broker? Can we not send to one of them? Is state or message redundant? Can one of them be derived from another? If we think of messages as events or as changes that affect state, then it becomes clear that state can be derived from events. Thus, only the communication with the broker would be needed. The state can be queried from a log of changes represented by events. This is what event sourcing is about. You can read more about reliable events delivery here.

The code used in this example is here.